How to decode your utility bill

If you missed part 1 of this series on the surprising, infuriating business model of investor-owned utilities, read it here first.

Utility bills are runic texts, impossible to parse without insider knowledge or a well-written blog post.

That's on purpose, of course. Just like lawyers, hospital administrators, and dark wizards, electric utilities prefer if you don't know what they get up to all day or why their services are so expensive. Power companies want you to feel, well, powerless.

Nuts to that! We can overcome their obfuscation together by unpacking my own personal utility bill from the Consolidated Edison Company of New York.

Dr. Aarati was kind enough to add the lettered orange boxes I'll be referencing throughout this post.

Here we go.

Page 1 of 3

The first page shows how much I owe for the pay period of March 26 to April 24, 2025.

I suspect my electric bill is lower than yours. Maybe even a lot lower. Per the EIA, the average American utility bill in 2024 was $144. If you live in Hawaii or Connecticut, apologies, friend: you're paying the highest prices for electricity in the nation. That's because Hawaii procures most of its energy from petroleum-fired generators that burn 'distillate fuel oil'—basically diesel gas, which is super inefficient—whereas Connecticut pays a premium to pipe their natural gas in from out of state. Both states, to their credit, have committed to achieving 100% renewable generation by 2045 and 2040, respectively.

Two reasons my bill is relatively low:

- We don't pay for heat. In New York City, landlords are legally required to provide heat to tenants from October 1 to May 31, also known as 'heat season'. Depending on whether or not your apartment has a metered thermostat, the cost of that heat may or may not be included in your rent.

Heating and cooling account for a whopping 44% of the total energy used by residential buildings in the U.S. They also make up 20% of our overall greenhouse gas emissions.

In my rent-stabilized, pre-war building, the heat's on the house. There's a gas-burning furnace in the basement that geysers steam up to our three ancient radiators at such high pressure that they routinely spew water out of their nozzles onto the floor whilst making loud clanging/didgeridoo sounds. Our apartment's radiators run real hot, so we end up keeping our windows open for most of the winter.

There's a surprising reason radiators in old New York buildings are so big and hot: it's because of the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918. Officials at the time wanted to promote fresh air circulation (evidently a new concept at the time), so they purposefully oversized apartment radiators to encourage tenants to keep their windows wide open all year long. Later on, when those buildings switched from burning coal to natural gas, our radiators got even hotter. Good times up here on the fourth floor. - My one-bedroom apartment, which I share with my partner, is not overly spacious, per se. Some might call it cozy. But the joke's on you, 'real America': we actually like constantly getting in each other's way, fighting for slivers of personal space and bathroom access. Plus, it's small enough that we only need one window A/C unit to stay cool, which helps keep the bills low.

Let's take a look at Box A.

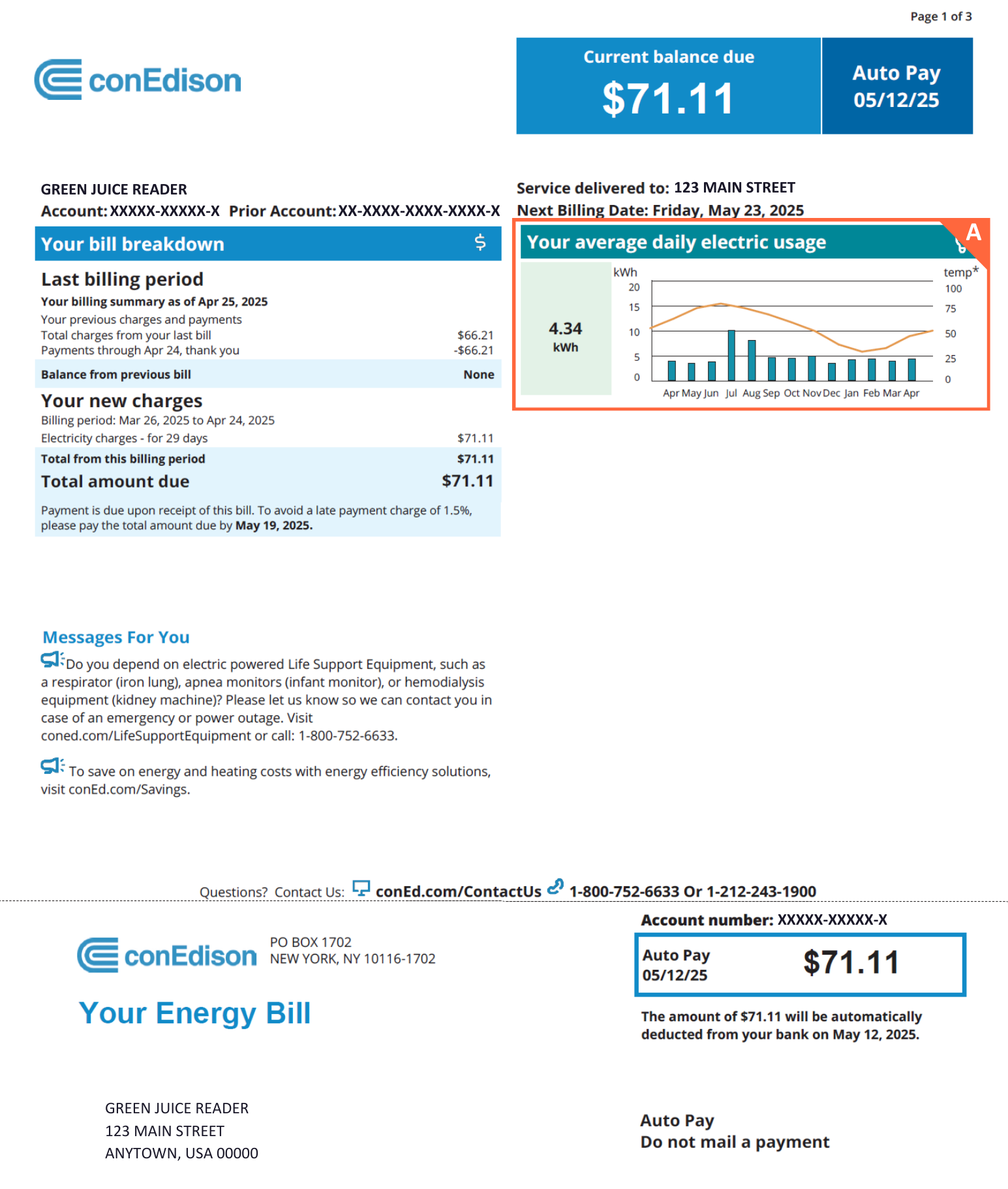

Box A: Average daily usage

This chart shows the correlation between our daily energy consumption, measured in kilowatt-hours, and the outdoor temperature. Unsurprisingly, we use more energy when it's hot outside.

4.34 kWh is the average amount of energy we demand every day. You might recall from my energy metrics explainer that the average American household uses 30 kilowatt-hours a day.

By comparison, 4.34 kWh is peanuts! However, we did hit 10 kWh a day during a sustained heatwave last July, so it's not hard to see how a bigger home with central A/C could get to 30 kWh.

The amount of energy we use may vary, but what about how much we pay for it?

To find out, let's turn to page 2.

Page 2 of 3

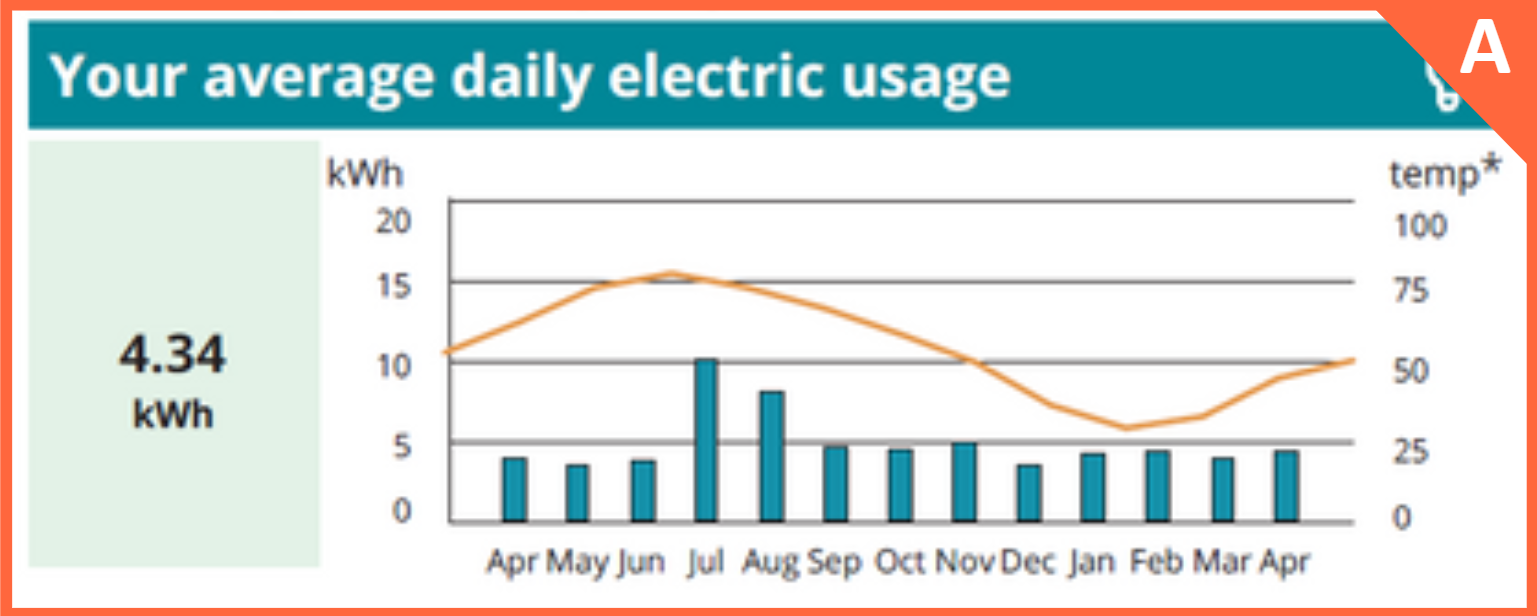

Page 2 is where things get interesting. Con Ed divides our bill into two itemized categories: Supply Charges and Delivery Charges.

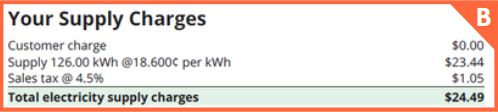

Box B: Supply Charges

Calling this 'Supply' is somewhat misleading. If you read last week's post, you know that Con Ed doesn't actually generate the electricity they sell. In fact, they're legally prohibited from owning any form of power production.

So instead, Con Ed purchases electricity on their customers' behalf from 'wholesale energy markets'. These markets mostly consist of 'Independent Power Producers' (IPPs), i.e. companies that operate natural gas plants, nuclear plants, hydro, solar arrays, and wind farms. There are some 400 IPPs in New York state.

The $23.44 Supply charge above tells us the amount of electricity Con Ed bought on our behalf this month (126 kilowatt-hours) as well as the price they paid for it (18.6 cents per kWh).*

The rate Con Ed pays changes every day. How that rate gets determined is a fascinating but complex subject.

(Trigger warning: acronyms)

- Most of the buying and selling of electricity takes place on what's called the 'Day Ahead Market' (DAM). Every day, utilities like Con Ed forecast how much energy they think their customers will need for each hour of the following day. Con Ed also calculates the maximum price they'd be willing to pay for that electricity, which will vary depending on the hour. Electricity, as we know, is cheap during the middle of the day and expensive in the evening.

- The Independent Power Producers (IPPs) likewise forecast the total number of megawatts they can each provide for every hour of the following day, along with the minimum amount of money they'll accept for one megawatt at any given hour.

- Both Con Ed (and all the other buyers, which are known as 'Load-Serving Entities', lol) and the IPPs send their forecasts to an organization called the New York Independent System Operator (NYISO), which manages the DAM. NYISO looks at all the data, then starts matching up supply offers with demand bids.

- But it wouldn't be fair if some buyers got cheaper power than the others, so NYISO uses a system called the 'uniform clearing price' (UCP) to help keep things equal. This concept is tricky, but it's important for a reason we'll get to in a moment. Here's a definition of the UCP, which I've cleaned up for clarity:

In selecting the power generators, the NYISO begins at the lowest (cheapest) offer and progresses through the higher offers until there is enough energy generation to meet all the forecasted demand. However, each selected bidder (i.e. Con Ed and the other buyers) is awarded the bid price of the last unit chosen (which will always be the highest (most expensive) of all the selected bidders).

Basically, the NYISO starts by assigning the cheapest megawatts and progresses to the more expensive ones until all the bids are met. But instead of some companies paying a lower price and others paying more, every buyer has to pay the price of the final IPP chosen, which will naturally be the most expensive.

Here's a very simplistic example of why this matters. Let's say 10 power producers submit offers to the Day Ahead Market—4 gas plants, 2 wind farms, 2 solar farms, and 2 hydro facilities. Each of them says they can supply 5 megawatts at 3pm tomorrow. Each also sets the minimum price they'd accept for a single megawatt at 3pm, based on how much it will cost them to generate the power and how much they think they can get for it.

The gas plants all set their minimum prices at around $50 a megawatt, the wind farms at around $30, the hydro at around $20, and the solar at around $10 (it's forecasted to be a beautiful day).

Let's say Con Ed and a dozen other buyers want to purchase a total of 40 megawatts for 3pm tomorrow. NYISO compares the data and starts to match power producers with buyers. They start with the cheapest—the solar, wind, and hydro—and work their way up. But since there's more power available (50 MW) than the buyers need (40 MW), two of the gas plants won't end up getting picked at all. So sad for them.

However, because of the uniform clearing price, Con Ed and all the other buyers will still have to pay $50 a megawatt, since that's the price of the last chosen bid—one of the two gas plants they need to meet the demand.

Okay, so now imagine there were 4 wind farms instead of only 2. In this new scenario, Con Ed and friends would end up only paying $30 a megawatt, since the last bid chosen would now be a wind farm. None of the gas plants would get picked.

The point is that building more renewable energy can bring down the price of energy markets, and therefore the price of our utility bills, since the utilities resell that power to us at cost. Abundant, cheap renewables put pressure on gas plants to bring their prices down or risk not winning bids. And if they can't bring their prices down low enough, they might just have to throw in the towel.

Of course, it's not always that simple. California's got the most solar on the grid of any state in the country, and yet Californians pay some of the highest utility bills. This is due to a number of reasons that I won't get into now—the situation over in California deserves its own post—but one common through-line is that we ratepayers end up footing the bill for a lot more than just electricity.

On that note, let's turn our attention to Delivery Charges.

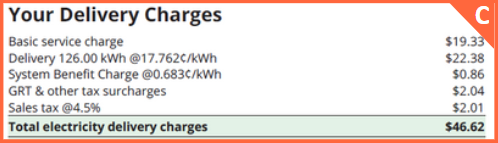

Box C: Delivery Charges

'Delivery' refers to Con Ed's role in sending the electricity they purchased for me to my house. It's not a direct role they're playing—no one's sitting behind a computer pressing a big button when I want to watch TV—but they are responsible for maintaining and upgrading the intricate grid system through which electricity runs.

For this ongoing service, they charge a Delivery Rate of 17.762 cents for every kilowatt-hour. In contrast to the fluctuating Supply Rate, the Delivery Rate is fixed: it can only change if Con Ed proposes a rate hike and that rate hike gets approved by New York's Public Utility Commission.

How often does Con Ed propose new rate hikes? As often as they possibly can, of course! After getting approval for a 13% increase over three years in 2020, they asked for and received another 12% over three years in 2023. Right now, Con Ed's attempting to raise their electricity rates yet again by another 11.4%.

They're trying to justify the latest rate hike by citing rising property taxes and the need to build more grid infrastructure. What I find weird is how they never mention needing more money to pay CEO Tim Cawley, whose total compensation was $15 million in 2024.

Anywho, let's go through the Delivery Charges.

The basic service charge

This is a fixed fee that Con Ed says covers 'basic system infrastructure and customer-related services, including customer accounting and metering services.' I thought infrastructure was funded by the Delivery charge, but okay.

The Delivery charge

So what does this pay for, exactly? The answer is that we don't know. But since it's not listed anywhere else on the bill, the Delivery charge probably pays for lobbying public officials not to build clean energy projects or reduce our deadly dependence on natural gas.

The system benefit charge

This charge funds public policy programs that focus on energy efficiency, renewable energy development, and energy education initiatives. Which explains why it's by far the cheapest line item on the bill.

The Gross Receipts Tax (GRT) and other surcharges: These are 'taxes imposed on Con Edison's gross receipts from sales of utility services.' So, state-mandated taxes and charges that Con Ed collects. I was unable to verify any specifics here about where this money goes. Possibly it funds the state's Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), which is supposed to increase our clean energy buildout.

You got all that?

Great. Now let's throw in a wrench in things.

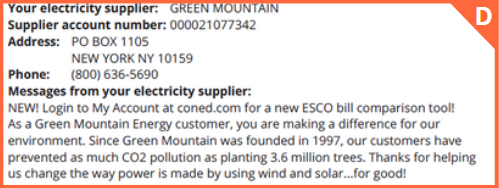

Box D: What's Green Mountain ???

Remember when I said wholesale energy markets 'mostly consist' of Independent Power Producers?

That's because there are a few alternative ways to procure power here in New York. One of them is called Green Mountain Energy, an Energy Service Company or 'ESCO' I'm under contract with that supplies our apartment with 100% renewable energy.

Well, sort of...

But I think that's enough for today! I'm trying to keep these posts manageable.

One last thing, tho: I'd really love to hear your feedback about Green Juice! Are these posts, in fact, manageable? Do you want even more? A little less? Maybe a mix of deep dives and shorter content? Let me know: jon@greenjuice.wtf

Member discussion