We need to upend our energy system in the next 5 years

The most complex machine ever made

In America, power flows in one direction: from the top down.

No, this isn't a recruitment pitch for DSA (though you really should join DSA). I'm talking, of course, about the electricity grid.

Our electricity infrastructure has been entrusted to a handful of utility companies ever since Tommy Edison built the first commercial power plant on Pearl Street in NYC back in 1882. The Pearl Street Station featured six coal-burning dynamos capable of illuminating a whopping 400 lamps.

We've come pretty far since then. But structurally speaking, things haven't changed all that much.

Here's how our energy grid works:

- Most electricity is still generated at big, industrial power plants

- That electricity gets sent from those plants to local distribution centers via miles and miles of high-voltage power lines. This process is called Transmission.

- When it reaches the distribution centers, machines called transformers turn the electricity's voltage down a few notches so it doesn't explode when it reaches its final destination

- The slightly more chill electricity traverses a vast array of wires to reach nearby houses, Costcos, laser tag facilities, etc. This process is called Distribution.

Simple enough, right? But if we pause to consider the intricacy of this system we've built, which provides instantaneous power to hundreds of millions of Americans day and night at the flip of a switch with remarkable reliability—if we consider that the energy grid must remain perfectly balanced at all times, with the amount of electricity generated always and exactly equalling the amount of electricity demanded—if we consider that our energy grid is not actually one grid but three distinct geographic grids operating independently with minimal interconnectivity—what we must conclude is that the American energy grid is nutso. The grid is a miracle. The grid, according to folks who know, is the most complex machine ever made.

You can understand why we've centralized the grid's operations: this sprawling machine is way more intricate and precarious than most of us realize. The people who operate it barely understand how it works. Everybody is afraid of fucking it up.

Therefore today 166 for-profit electric utilities are responsible for transmitting and distributing power to more than 70% of the country. These utility companies monitor the grid's health, foster its growth, and decide which new energy projects get to plug into the grid and which don't. They are state-sanctioned monopolies, conservative in nature, though by no means averse to making money.

Thus, power flows from the top down.

The limitations of centralized control

This top-down model has served us pretty well. For a long time, electric bills stayed mostly flat and the lights stayed mostly on, so we didn't think too much about it.

But a confluence of recent events has changed all that.

Unprecedented growth

America today is experiencing the most 'load growth', i.e. an increased demand for electricity, of any period since our boys came back from World War II with spending money in their pockets and a gleam of vast suburban sprawl in their eyes.

Some of today's new demand arises from the ongoing and necessary work of Electrifying Everything—our transportation, homes, and industries—and theoretically powering them all with renewable energy. This is the crux of the 'energy transition,' the deliberate forsaking of fossil fuels in favor of a world powered by 100% solar, wind, batteries, and other clean energy technologies.

But there's an even bigger fish that's gobbling up our grid's resources. An insatiably hungry fish that doesn't care how it gets power so long as it can feed. I'm referring, of course, to data centers. Whether you're in favor of AI girlfriends or not, a slew of data centers are coming. In fact, they're already here, wreaking havoc on our most vulnerable cities and citizens. See, for example, Elon Musk's xAI in South Memphis, powered by 35 methane gas-burning power plants, none of which have been equipped with pollution controls. Nearby residents report being unable to breathe.

Stopping all this from happening is not currently realistic. Hell, even regulating the growth of these data centers is unlikely to happen under our current administration. It's a free-for-all out there.

This could end badly for any number of reasons. But there's one in particular I want to bring to your attention: In order to power the many data centers coming online over the next five years, experts believe we will need to build something to the tune of 150–200 gigawatts of new electricity generation.

Some context for those numbers: a nuclear reactor—the single largest power producer we have—generates one gigawatt. We will decidedly not be building 200 new nuclear reactors over the next five years. Nuclear plants take a decade (at least) to build, and they're incredibly expensive.

Speaking of big expenses...

An affordability crisis

One in six Americans today cannot afford to pay their utility bill.

Unfortunately, the price of our utility bills is only going up, up, and up. For the foreseeable future.

Things will get especially dire if we ratepayers (i.e. everyone who pays a monthly electric bill) end up subsidizing the energy needs of all these new data centers, which is a very real possibility—one our tech overloads are currently conspiring with these same utility companies to sneak into existence before the public even knows its happening.

It didn't have to be this way. Jigar Shah, an esteemed figure in the clean energy world, recently spoke on the DER Task Force podcast about how utility companies spent the last twenty years—a fallow period of flat energy growth during which they really should have been preparing for the present moment—choosing instead to appease their shareholders:

People want to pay their electricity bills, but when you get a surprise bill thats $200 more than you expected it to be, sometimes you don't have the budget to pay for that. And that's your fault as the utility—it is your fault as the utility to not comprehend that for twenty years, when you had a good thing going and you were running up the score on purpose because you could not meet your earnings-per-share for your shareholders. And now all of the employees that work at your company have been trained for twenty years to run up the bill. But now shit's old. And you gotta replace stuff.

The people who work at Con Ed raised rates another 12% this year. Why? Because they could not believe in their wildest dreams that they could take a battery through the FDNY and go to all the parking garages and be like, 'We just want one of your spots, we'll pay you triple,' and stick like a zinc halite battery from Eos in there. That would have been one-tenth the cost of the 12% rate increase. But that's not culturally something they can do.

But we're getting ahead of ourselves. There's one more culprit we need to acknowledge.

The death cult of Big Dystopia

Ah, yes.

The Trump administration is all in on destroying the clean energy movement in this country. Yet the alternatives they offer us are no real alternatives at all:

'Build more coal power plants' is an insane suggestion. It's fundamentally flawed, and just not because coal is the dirtiest fossil fuel. Coal plants are extremely expensive to build and operate, especially compared to renewables and even gas-fired power plants. The economics (not to mention the optics) are so bad that nobody does it anymore. The world is moving on from coal. There hasn't been a new coal plant built in the U.S. in over ten years.

'Build more gas power plants,' Trump's other big idea, cannot happen because of global supply chain bottlenecks that will severely limit our capacity to build new gas plants for the next five to seven years.

On the same podcast I mentioned earlier, Tim Hade, another respected energy figure and the cofounder of Scale Microgrids, told an anecdote about how he recently paid a visit to the Head of Policy at the American Gas Association. Tim asked the guy, whose name is Richard Meyer, how many gas turbines we could deploy in the U.S. in the next five years, given the supply chain issues, in the best case scenario?

Meyer's optimistic answer was 50 gigawatts worth of new gas plants.

To be clear, in an ideal world we would not be building any new gas turbines ever again. But the precarity of our present moment demands we build as much new power generation as we possibly can as quickly as we can, because the alternative surely means rolling blackouts, more people dying in their homes during increasingly severe heatwaves, the collapse of civilization as we know it, etc. etc.

So. Let's say Richard Meyer is right and we manage to build 50 GW of new gas plants straightaway. Even then, we will still have something like 100 to 150 GW of new power generation to account for, assuming all the new data centers get plugged into the grid.

So how on earth do we do that?

Good ideas that won't work

Build more transmission lines?

Sure, in theory we could build a bunch of new high-voltage transmission lines all the way out to the sunny southwestern corner of this country, which would enable us to construct vast solar fields to feed into the grid. We could build transmission lines to the windy Midwestern plains, where Kansas alone could likely meet our energy needs if we built enough new wind turbines. There are even ways to skirt some of the more annoying issues with building new transmission lines, such as getting dozens of small landowners and neighboring states to sign off on projects, by building the lines along interstate highways or, my preference, alongside railroad tracks, both of which have legal 'right-of-ways'.

Honestly, that would rock. We could have electrified trains in this country. But it's not gonna happen anytime soon. It's really difficult to build new transmission even in the best of times because it is super-duper expensive. To build at the scale we need would require a massive investment from the federal government, which... yeah.

There are, however, very useful and relatively inexpensive things we can do to get more capacity out of our existing transmission lines. Utilities can and are starting to do some of this stuff, broadly known as 'grid-enhancing technologies,' which have cool names like 'reconductoring' and 'advanced power flow control.' But these fixes don't increase the range of our transmission lines. Unlocking new renewable regions would require lots and lots of building.

What we need is to build renewable energy projects in places where the grid already goes.

More utility-scale renewables?

Look, I'll never argue against building more giant solar and wind farms. But that's not a viable solution in the short term, either.

Not because we don't have the room for it, mind you. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) estimates there's potential for 5,750 GW of utility-scale solar on 44 million acres of federal land alone, plus another 2.2 to 15.1 terawatts (1 TW = 1,000 GW) of onshore wind farm potential.

So why not go ham on huge solar farms? Because at long last we've reached the limitations of our top-down system. It is not enough to build a solar farm. You've gotta plug that sucker into the grid. And to do that, you better get in line.

It's what every New Yorker hates and fears most: waiting on an insanely long-ass line. The line to get into Club Grid is called the 'interconnection queue,' and believe me when I say it is fucked.

As of December 2023, there are 2.6 terawatts (2,600 gigawatts) of solar, wind, and battery storage projects idly waiting for approval from their local utility company to get plugged into the energy grid. These projects will not begin construction until they get their approval, which will take them up to three years.

Three years!

It's so difficult to put your business plans on hold for three whole years. And even if you get approved, there's a good chance you'll be told you need to spend millions of additional dollars upgrading transmission lines to support your project. The utilities don't have the capacity or the money to do it, and they know that someone in the huge line is impatient enough to foot the bill. This arrangement is so bad that the vast majority of projects never make it.

Here's a slightly dated but still relevant Canary Media article on this subject:

The proposed wind, solar and battery projects seeking interconnection to U.S. transmission grids today are enough to bring the country to 80 percent carbon-free electricity by 2030. But based on historical trends, less than a quarter of those planned projects are likely to be built.

And even the best-positioned projects that already have the land rights, construction financing and power-purchase contracts necessary to move forward are likely to face years of delay and potentially millions of dollars of grid upgrade costs before being able to connect to the grid. These barriers could prevent many planned projects from reaching completion — and block the country from decarbonizing fast enough to prevent the most devastating effects of global warming.

How is this real life?

Capitalism, mostly! But also partly because the grid, as mentioned at the top of this article, is more fragile than most people realize. Plugging hundreds of new megawatts into the system could overburden aging transmission lines, thereby causing blackouts and explosions, etc. etc.

But the real reason is that the top-down system under which we operate has hit its ceiling. When power is concentrated in the hands of the few, there is a hard limit to what it can effectively manage. We simply do not have the capacity for a 21st century grid to be run like Thomas Edison's Pearl Street Station.

So what do we do?

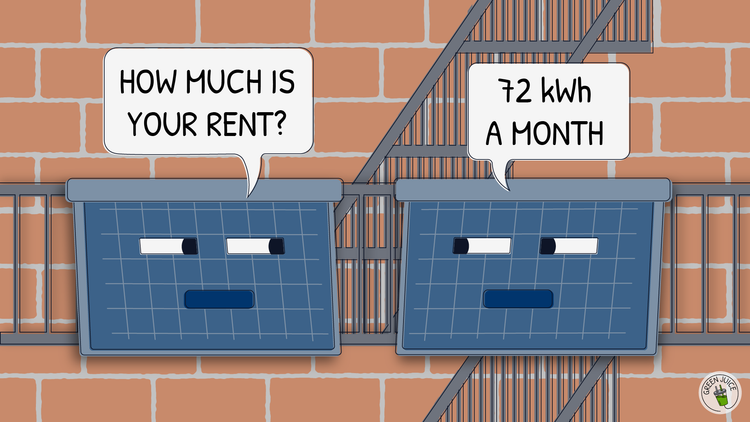

We give the power back to the people.

Member discussion