The surprising, infuriating way electric utilities make money

Today we're taking a medium-deep dive into the polluted waters of everyone's de facto favorite state-sanctioned monopoly: the investor-owned utility company.

Hold your nose and dive in!

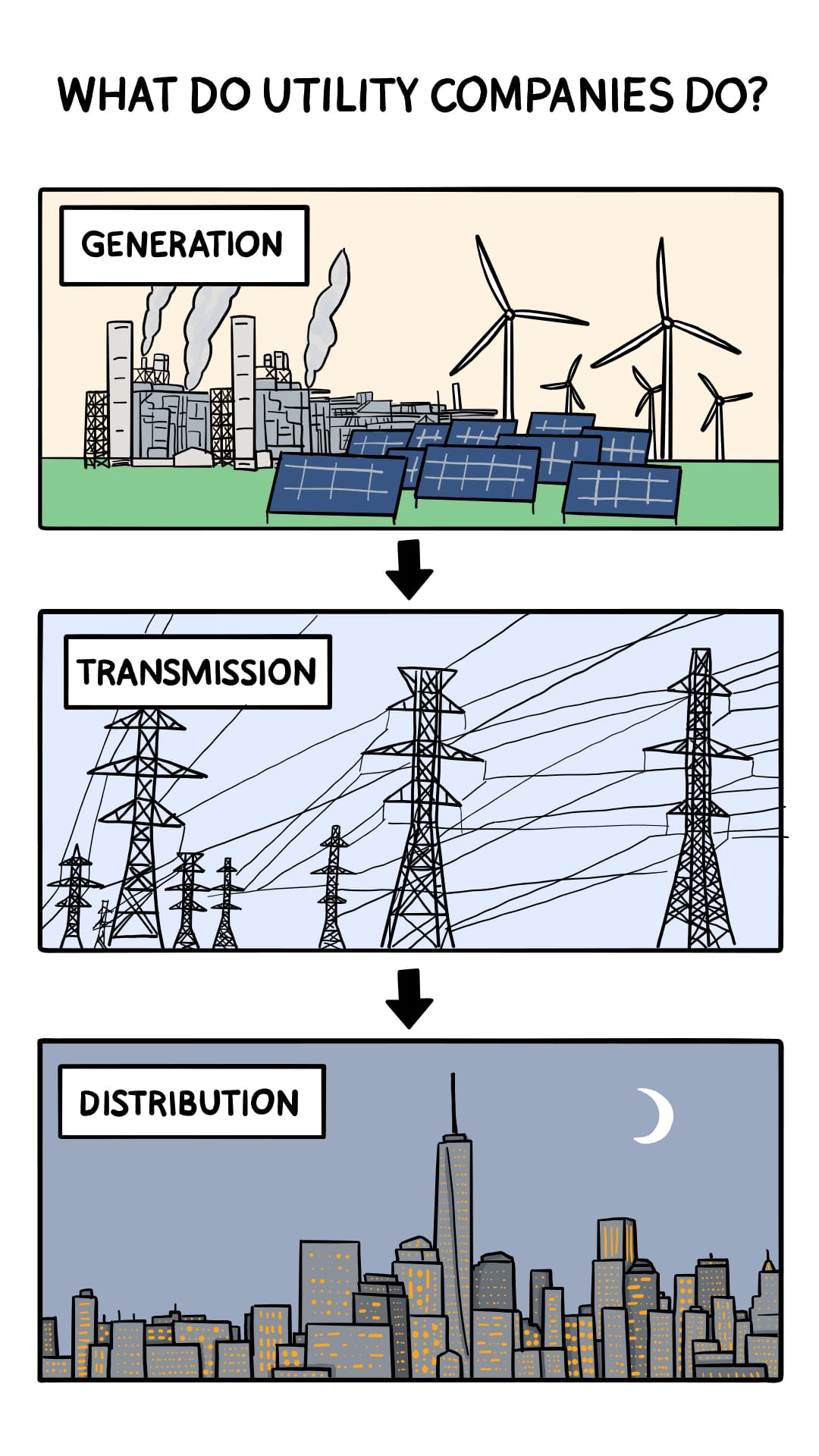

1. What do electric utilities actually do?

Electric utilities have three basic functions, though only some of them are allowed to do all three.

Build generation

'Generation' refers to things that produce power like gas plants, wind turbines, and solar farms.

Manage transmission

'Transmission' refers to sending electricity along high-voltage power lines from wherever it's generated to a substation near its ultimate destination.

Manage distribution

Once the electricity arrives at the substation, it gets 'stepped down' i.e. made less powerful, and is then locally distributed via lower-voltage power lines. In some densely populated places, these power lines are buried underground.

As mentioned, not every utility does all three. Many electric utilities are legally prohibited from building or owning any form of power generation—they're only allowed to 'manage the wires', i.e. build and maintain transmission and distribution (T&D) infrastructure. The rules are different depending on state regulations and who owns the utility.

2. Who owns the utilities?

Electric utilities are either publicly owned and run as not-for-profit or privately owned and run as very-much-for-profit.

Publicly owned utilities (POUs)

Owners can be a local cooperative, a municipality, or a statewide governing body. Cooperatives are more commonly found in rural places, but recently there have been some exciting developments around the country related to communities opting out of their investor-owned utilities and instead procuring their own power.

Investor-owned utilities (IOUs)

Investor-owned utilities serve some 72% of Americans. They are state-sanctioned monopolies that exist to make as much money as possible for their estimable shareholders.

In the Southeast and Northwest, most IOUs are considered 'regulated monopolies', meaning they can build power generation and manage transmission and distribution. This is the 'vertical integration' model—the utilities are allowed to control all aspects of the energy process.

Elsewhere, including in New York, Texas, and Illinois, IOUs operate in a 'restructured market', which means they're legally prohibited from building power generation: they can only build and maintain the physical infrastructure of the T&D networks, i.e. gas pipelines, power lines, substations, transformers, etc. This is intended to be an anti-monopoly safeguard.

What this means is that if you live in New York and your electric utility is Con Ed, you're not actually getting electricity from Con Ed directly. Rather, Con Ed buys electricity on your behalf from a 'competitive wholesale market' and then oversees its delivery to your home.

3. How do IOUs make money?

Here's where things get interesting. Investor-owned utilities don't make money by selling you electricity. Instead, they make all their money by building new stuff. How? Every time they build something, they get paid a fixed percentage of the overall cost of the project. This is called a guaranteed rate of return (or a 'return on equity'). It's guaranteed by the state, but we—the duly named ratepayers—pay for all of it.

Here's an example. Let's say your electric utility's guaranteed rate of return is 10%. They get approved to build a $10 million gas pipeline. They are therefore guaranteed a million dollar payout on top of the $10 million they're getting to do the project. That million dollar payout is given to them no matter how long the project takes or how good (or bad) a job they do. And, yes, ratepayers foot the bill for all $11 million. The $11 million debt we incur gets spread out over the 'useful lifetime' of the project.

FYI, the average rate of return for IOUs in 2023 was 9.6%.

4. Wait, so utilities can only make money by building stuff? Isn't that, like, kind of dumb?

Indeed it is. The business model made more sense 100 years ago, back when America needed to rapidly build out the energy grid.

Not so much today. The problem with getting paid a fixed percentage of a project's total cost is that it heavily incentivizes you to build lots of expensive projects.

One common tactic IOUs like Con Ed use to take advantage of their guaranteed rate of return is to fully replace leaky (or even just old) gas pipelines, instead of attempting to repair them. They don't get paid for making repairs! So they automatically replace whatever they can. This is not only expensive, it also resets the lifecycle of gas infrastructure, thereby locking us into another 50 years of natural gas dependency.

Maybe replacing old pipelines doesn't sound so terrible. The issue is the scale at which they operate. Con Ed's reported revenue in 2024 was $15.26 billion. That's a lot of pipes we're paying for.

And trust that we are paying: 21% of New Yorkers' monthly utility bill goes directly to Con Ed's profits. Is that enough for them? Not under capitalism, baby! Con Ed is, at this very moment, trying to raise their rates again for the third time in five years.

If you're a Con Ed customer and feel so compelled, I encourage you to leave a public comment about why (and how?) Con Ed's latest proposed rate hike can go fuck itself.

5. Perverse incentives

If you only get paid to build, your incentives may not align with what's best for the general public. There's a name for this: 'perverse incentives'. Here are two ways that the IOU business model ends up hurting the rest of us:

1. Even if IOUs can't build power generation, they still have an obvious interest in making sure we all continue to use lots and lots of electricity. Why? Because it justifies building more infrastructure. This makes utilities a natural enemy of anything that reduces energy use in the near- and long-term, such as clean energy technologies like heat pumps and home insulation and efficiency programs.

2. IOUs are likewise opposed to any form of decentralized energy procurement and storage, because this also reduces the need for them to build large-scale infrastructure projects. I haven't written much about Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) yet, but the basic idea is that if lots of people with rooftop solar panels and home batteries got together, they could all put a little bit of energy into one big pool. That pool of energy could be used to make sure the grid stays balanced. A big network of aggregated DERs would prevent blackouts, improve community resilience, and keep electricity prices down.

One more note on DERs: it doesn't just have to be homeowners with rooftop solar panels pitching in. You can stick solar panels on top of schools and hospitals and public housing and parking lots. There's a community-first vision of a DER-centric future that I am quite drawn to, in which we literally take the power away from these profit-motivated corporations and put it in the hands of the people.

6. How do IOUs oppose clean energy and DERs?

Oh, just by spending our money on lobbying politicians not to pass climate bills.

Con Ed spent $640,000 in 2024 on federal lobbying, an undisclosed amount of which came from ratepayers. They're also a member of trade associations like the conspicuously named Edison Electric Institute (EEI), which spent $779,400 in 2023 on 'advocacy'.

Con Ed's also got their own Political Action Committee (PAC), funded by employees and shareholders, so they can make donations to specific candidates and campaigns. For instance, they sent $67,000 to good old Governor Hochul (including $10,000 in contributions from CEO Tim Cawley).

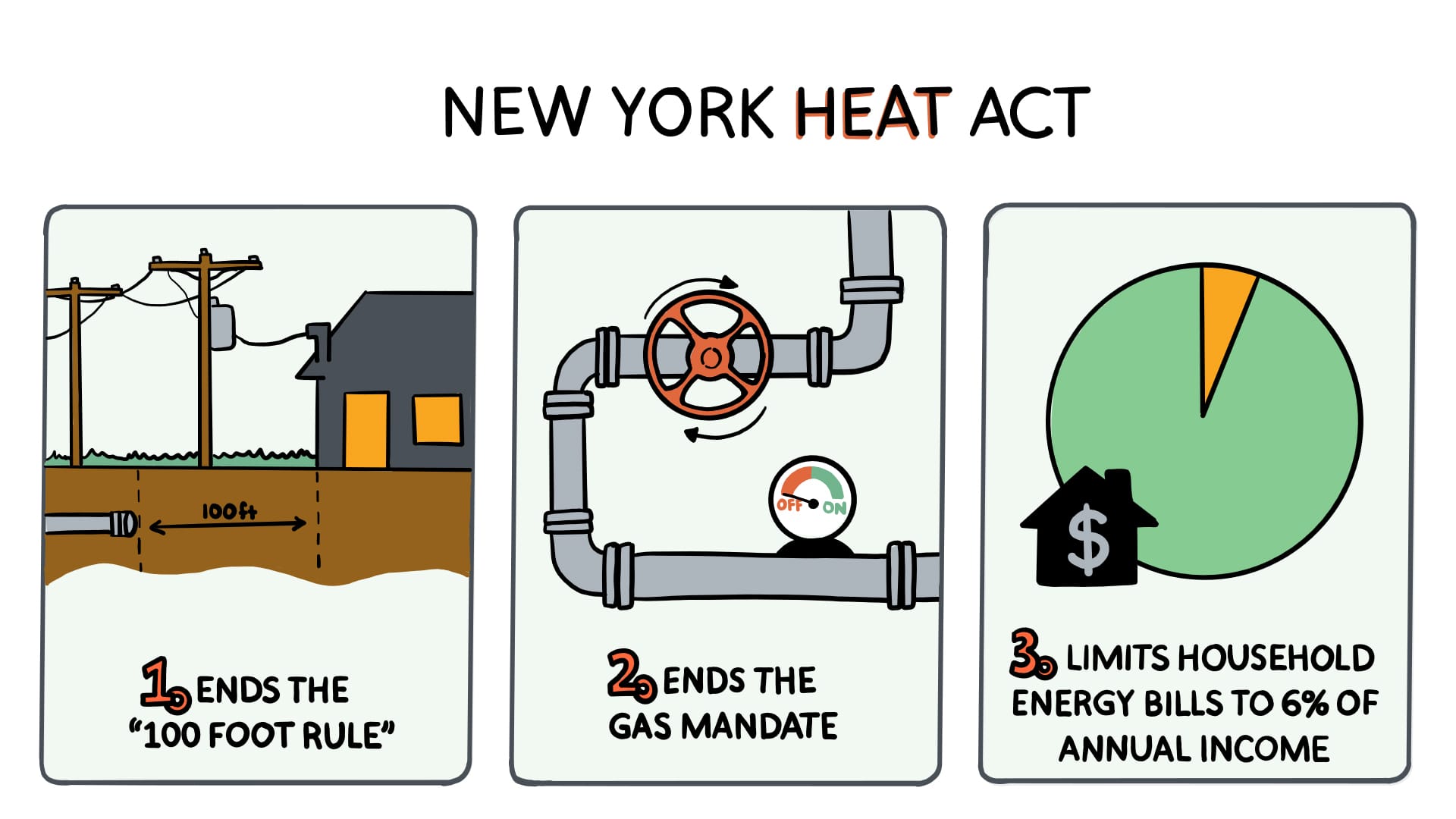

Maybe now's a good time to mention the NY HEAT Act. This common sense climate bill just failed to make the state budget for the third year in a row. It's a real shame, because the HEAT Act would have done three very good things:

- End the '100 foot rule' that allows utilities to automatically hook up new buildings to gas lines if they're located within 100 feet of an existing gas main. Ratepayers shell out $200 million a year for this.

- End the 'obligation to serve', which says utilities must oblige anyone who requests natural gas service. Ending this 'gas mandate' would make it much easier to plan renewable energy-powered communities.

- Cap energy bills at 6% of a household's income, which would save the 25% of energy-burdened New York residents an average of $136 a month.

But there's always next year, right?

I should note that Con Ed is by no means alone in lobbying for their own interests. Electric utilities nationally donated $115 million to state-level candidates and political parties during the 2018 cycle.

7. Who approves the new projects?

Since they're state-granted monopolies, IOUs are regulated by the state. In theory.

Every state in the U.S. has what's called a Public Utility Commission (PUC), a regulatory body with the power to approve or deny proposed utility projects. In most states, PUC commissioners are appointed by the governor. In 10 states, they're publicly elected.

PUCs are arguably the most powerful, least known regulatory bodies in the country. There are just 200 PUC commissioners who collectively oversee $200 billion in utility spending every year. If my math is right, that's a billion dollars per person. Meanwhile, some of these commissioners are only making $60k a year.

To put it mildly, this situation creates the potential for 'regulatory capture'. It is not at all uncommon for PUCs to be staffed by former utility company employees, or for commissioners to join utility companies as soon as their terms are over.

Nascent efforts are being made to elect and appoint climate champions and utility reformers to state PUCs. The PowerLines organization is doing important work on this front: they just launched a PUC jobs board, so if you've got any engineering, economist, or lawyer friends with incorruptible backbones, consider advising them to make a real impact on how our money gets spent.

Member discussion