A real-life ghost story

Gather 'round the campfire, friend, for I've a spooky story to tell this Halloween week.

A ghost story. A true one.

Goes like this.

Deep below the grassy plains of eastern Montana and North Dakota, stretching well up into Canadian Saskatchewan and Manitoba, lies the fathomless remains of one of the largest mass extinction events in the history of the world.

Undisturbed for millions upon millions of years, until their discovery by oil drillers in 1951.

It's been hell on Earth ever since.

To understand the story—to approach even an inkling of understanding—you must cast your mind back into the aether of prehistory. To a time far beyond the days of our earliest ancestors.

The Late Devonian mass extinction

Our story begins 372 million years ago, during what's today known as the Late Devonian period. The Earth looked different, then. There were only two continents: Euramerica in the north, Gondwana in the south. They had yet to collide and form the great supercontinent, Pangaea, the mother of our modern world.

In the Late Devonian, much of the planet was covered in vast, epicontinental seas.

Seas that teemed with life. Sea creatures, millions upon millions of them, formed and populated extensive coral reefs that filled the oceans like cities.

Horseshoe crab-like trilobites, spiral-shelled ammonites, bivalved invertebrates, reef-building sponges and corals. Jawless fish, unknown land animals, unknown life forms. The creatures we know, we know from their fossils.

But they are all extinct now.

For something terrible took place.

The first of two Late Devonian mass extinction events, the Kellwasser event, killed off 40% of all marine life on Earth.

The second event, the Hangenberg, followed 13 million years later. Together, some 70–80% of all species on Earth were lost, never to be seen alive again.

The Late Devonian mass extinction is one of the so-called "Big Five" worst mass extinction events ever discovered in our planet's long, bloody history.

How did it happen? Why?

It was an accident. Something new was taking root in the world, then: plants and trees had begun to evolve vascular systems for the very first time. These systems allowed them to spread to previously uninhabitable places. The root systems they could suddenly grow pushed deeper, until they found water. This in turn stabilized the Earth's soils, which then delivered their ample nutrients to the oceans whenever it rained. Over time, nutrients accumulated in great numbers. This triggered massive algal blooms that spread across the seas. Algae, floating on the surface of the water, blocked the sunlight from reaching underwater plants. When the algae died, bacteria colonies grew to eat them. These bacteria would consume massive amounts of oxygen.

The result was a condition known as marine anoxia—a lack of oxygen in the water.

And the whole world drowned.

Today, manmade global warming is causing our ocean temperatures to rise. This in turn drives changes to ocean circulation and ventilation. When oxygen-rich surface waters cease to mix with the deeper, more anoxic layers of the ocean, the deep layers become even more deprived of oxygen.

Consequently, we are on a path toward the sixth largest mass extinction event in history.

But that's not where this ghost story ends.

All the dead seas creatures

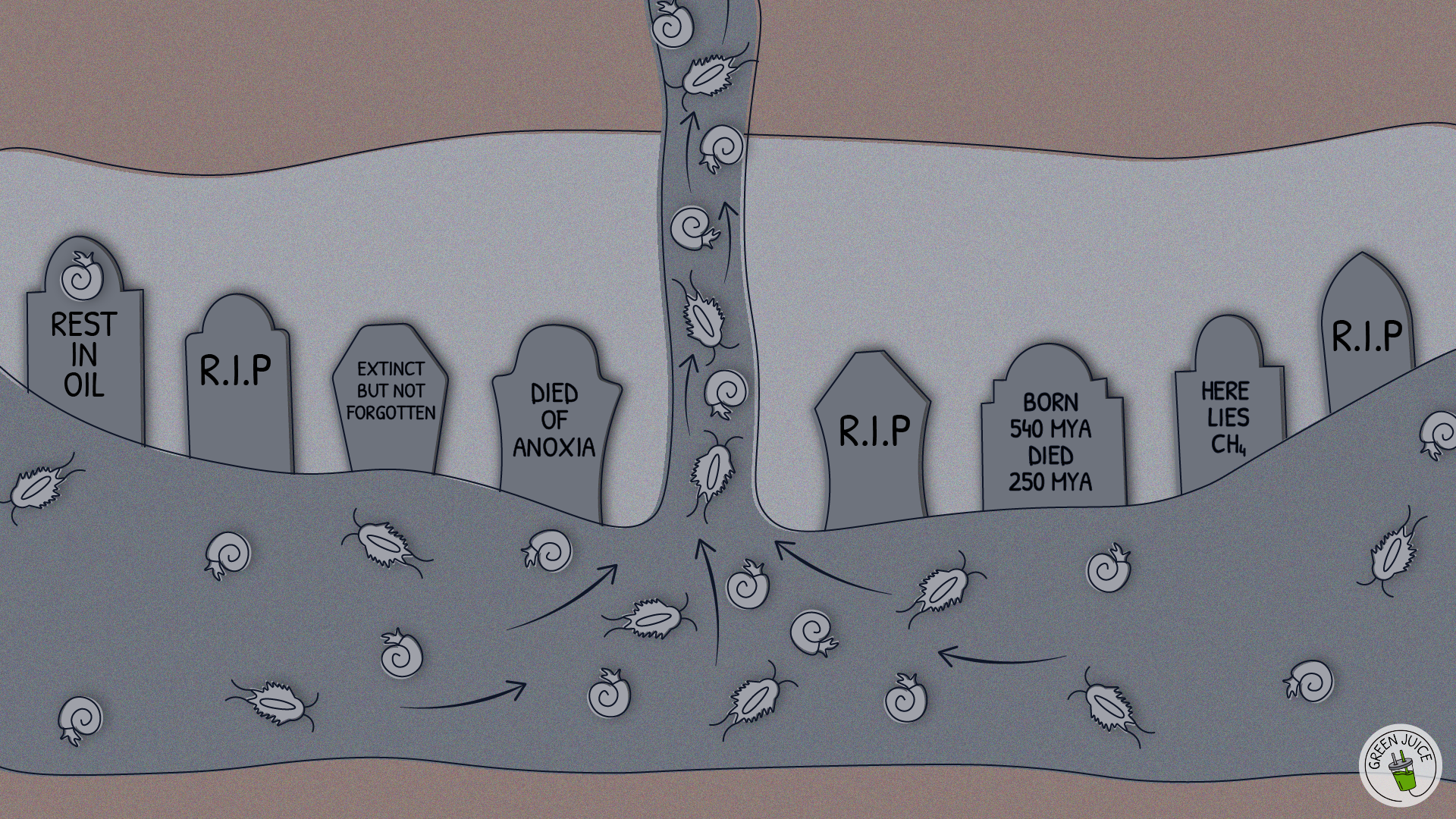

Picture it. Millions and millions of dead creatures of shapes and sizes you've never imagined, sinking like stones to the bottom of the sea.

But there is no longer enough oxygen at that depth for these creatures to properly decompose.

So there they remain, settled in the silt. Caught between worlds. Lifeless, but mostly intact. Ghosts, unable to return their energy to creation.

Millions of years pass by. No one is alive to notice. Still, the waves crash. Grain by grain, sediment accumulates atop the lifeless bodies. The weight of the sediment increases over time. Pressure begins to build. The pressure squeezes out any remaining water from the bodies. It compacts the organic material. It gets warm, and then hot.

Gradually, the bodies transform until they are no longer recognizable. The sea creatures become a material known as kerogen. Rocklike, but waxy and insoluble. Part sediment, part organic matter.

Millions of years again pass again. The kerogen gets buried deeper and deeper beneath the floor of the ocean. Pressure and heat further intensify.

Kerogen, exposed to sustained temperatures of 150–300 °F, turns into oil.

At even higher temperatures, kerogen turns into explosive gas.

Bodies in the basin

The Late Devonian mass extinction was a global event. No part of the world was left untouched.

But there are certain places, with certain geological conditions, where dead and inorganic things tend to accumulate.

One such place is known as the Williston Basin. It is a sedimentary basin, where nearly two billion years ago, a section of the planet sagged as the continent formed.

There, thousands of feet below the grasslands of Montana, North Dakota, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, pressure and heat turned dead animals into shale rocks rich with oil and gas.

The Williston Basin is filled with the deceased from the Late Devonian mass extinction.

It's called the Bakken Formation. Named for Henry O. Bakken, the farmer who claimed ownership over the land where it was discovered by oil drillers in 1951.

It spans 200,000 square miles, entirely below the earth's surface.

Try to imagine a world in which the discovery of a vast gravesite, perfectly preserved over hundreds of millions of years, was met with reverence, or awe, or grief. If ever such a world existed, it is not ours. It is not this.

Instead, the Bakken has become one of the most productive oil and gas deposits in all of North America.

More than one million barrels of oil are pumped each and every day from the shale oceans of the Bakken. Over three hundred billion cubic feet of "natural" gas is drawn every single day by hydraulically fracturing.

Setting the dead aflame

As recently as 2013, more than 30% of the fossil gas harvested from the Bakken was flared, or burned—destroyed—on purpose.

Why? Sometimes gas is flared if there isn't sufficient pipeline infrastructure to transport it away.

Other times, here in America, the wealthiest country on Earth, we destroy our own commodities in order to keep prices artificially high. Supply and demand. Economics 101.

"Natural" gas is almost entirely methane. When you burn methane (CH4), it combines with oxygen to produce CO₂ and H₂O.

Flaring gas therefore releases carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, into the air.

Still, that's preferable to releasing unburnt methane. Because methane gas accelerates climate change at a rate 80 times that of carbon dioxide.

Flaring, however, is imperfect. Some gas always escapes.

Using satellite technology, we can now study methane emissions from space. To no one's surprise, it turns out that we are once again being deceived by Big Dystopia.

A study from just last year:

Natural gas producers across the U.S. are emitting methane into the atmosphere at over four times the rates estimated by the Environmental Protection Agency for those same areas based on industry-reported data. The results also show that operators are exceeding their own widely touted emissions goals eightfold.

The Bakken Formation has been called a carbon bomb—that is, a fossil fuel site projected to release more than one billion tons of carbon throughout its operational lifespan.

And yet climate change is only one form of revenge the ghosts of the Late Devonian are taking.

How ghosts get revenge

The dead should be left to rest in peace.

When they're not, bad things happen.

The Lac-Mégantic rail disaster

On July 6th, 2013, an unattended 73-car freight train carrying Bakken Formation crude oil derailed in the town of Lac-Mégantic, Quebec.

Newspaper reports describe a 1 kilometer blast radius.

An explosion that killed 47 people. The deadliest non-passenger rail accident in Canadian history. Half the buildings downtown were destroyed. All but three of the remaining 40 buildings had to be demolished due to petroleum contamination.

The highly volatile Bakken crude oil had been mislabeled—perhaps on purpose—as lower-risk, less explosive oil, and shipped in tank cars not designed to contain it.

The blast site was so heavily contaminated with the chemical benzene that firefighters and investigators worked for an entire month in 15-minute shifts, due to the heat and toxic conditions.

The dark side of the boom

Between 2006 and 2012, new drilling and fracking technologies turned the Bakken from a minor player into one of the most productive shale oil formations in the world. In North Dakota alone, output increased from 200,000 barrels to 1.1 million barrels of oil a day, making North Dakota the second largest oil-producing state behind Texas.

The resulting boom meant quick money. Quick money meant a rush of men. A rush of men with quick money meant drugs, violence, and sexual assault.

Over the course of those six years, violence in the area increased 70%. For Black and Native American people, the rate of victimization was 2.5 times higher than for whites.

Men arrived from all over the country to drill for oil and gas. It all happened so fast. They quickly ran out of housing. But workers will not be turned away when there's money on the table. So they built man camps: roughshod, temporary compounds to support the flood of largely male oil and gas workers.

In the Bakken, man camps are often located on or near Native American reservations, such as the Fort Berthold reservation in North Dakota (named, insultingly, after a U.S. Army fort). Fort Berthold is home to the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, or the Three Affiliated Tribes.

Heroin and meth showed up in the man camps, where there's little to do and few places to spend money. The drug trade spread quickly to the reservations.

Legal scholar Ana Condes states that man camps are “hotbeds of rape, domestic violence, and sex trafficking, and American Indian women are frequently targeted due to a perception that men will not be prosecuted for assaulting them”.

Author Lily Cohen writes that “Native women face increased levels of sexual assault, sex trafficking, and other gender based violence when resource extraction projects are located near Native communities”.

Journalist Sari Horwitz wrote about the brutality that came to this part of the world in an excellent piece in the Washington Post, titled Dark side of the boom.

I quote from the piece:

“It’s like a tidal wave, it’s unbelievable,” said Diane Johnson, chief judge at the MHA Nation. She said crime has tripled in the past two years and that 90 percent is drug-related. “The drug problem that the oil boom has brought is destroying our reservation.”

Once farmers and traders, the Mandan was the tribe that gave Lewis and Clark safe harbor on their expedition to the Northwest but was decimated in the mid-1830s by smallpox. Over many years, the 12 million acres awarded to the three tribes by treaty in 1851 has been reduced to 1 million by the United States.

The U.S. government in 1947 built the Garrison Dam and created Lake Sakakawea, a 479-square-mile body of water that flooded the land of the Three Affiliated Tribes, wiped out much of their farming and ranching economy, and forced most of them to relocate to higher ground on the prairie.

“When the white man said, ‘This will be your reservation,’ little did they know those Badlands would now have oil and gas,” MHA Nation Chairman Tex “Red Tipped Arrow” Hall said in an energy company video last year. “Those Badlands were coined because they’re nothing but gully, gumbo and clay. Grass won’t grow, and horses can’t eat and cattle or buffalo can’t hardly eat . . . but there’s huge oil and gas reserves under those Badlands now.”

It's not too late to turn back from all of this. To let sleeping ghosts lie. To bind the jaws of Hell.

But I wouldn't bet on it.

The fossil fuel industry is a death cult

My friend and fellow Ecosocialist Harrison sums it up like this:

The fossil fuel industry is a death cult.

Our energy system runs on a dark necromancy. We plunder the putrefied ooze and gaseous decay of long-dead creatures. Dig them up just to condemn them to a second death, using what’s left of them to fuel an inferno. Is it any wonder the smoke of their tormented souls haunts the planet? Chokes our lungs with vengeful miasma?

It’s a hex on the world. An unholy exorcism. They torture nature and the planet thrashes in pain, smothering whole countries.

For what? For an inhuman thirst that can’t be quenched by the oil they greedily suck like vampires from the veins of the planet. They can only be satisfied by the purest concentration of the blood, sweat, and tears of billions: money. No amount is ever enough.

The real horror isn’t legends of ghosts and ghouls. The real horror is these acolytes of apocalypse looking down on us from their towers and private jets. The real horror is the fact that these apostles of hell are the ones in control.

I'd put it like this: we're awful quick to blame the ghosts for lashing out, when we're the ones who dug 'em up, put 'em on a train, sold 'em at market, and set 'em on fire.

Happy Halloween.

Member discussion