Finally, clean energy for renters

In the first post in this series, I argue it's high time we evolve beyond our centralized, top-down energy system, wherein a handful of for-profit utility companies control the lion's share of the electricity grid.

My case was unfortunately strengthened this week when Heatmap's Jael Holzman reported on an internal federal memo making the rounds in the halls of power. The memo, which Holzman calls a 'secretarial order', effectively puts the kibosh on any new wind and solar energy projects the government doesn't like. Which could very well be all of them.

The very next day, the New York Times reported that Republican Senator Josh Hawley just killed an $11 billion transmission line project that was about to begin construction. Known as the Grain Belt Express, the line would have brought clean Kansan wind energy to the greater Midwest, lowering energy bills and improving resiliency for millions of cornfed Americans. The project had been in the works for more than ten years, held broad bipartisan support, and had managed to get four states to agree to terms... and then Josh Hawley's evil, stupid ass set the whole thing alight by making a phone call to the Oval Office. Trump said, quote, 'Let’s just resolve this now,' and did.

Outrageous! Execrable! Intolerable!

What's a declining empire to do?

Widely distribute our energy system

The answer is DERs, duh

Get used to seeing the acronym 'DERs'—Distributed Energy Resources—because it's on a collision course with the zeitgeist.

You can spell it out—'Dee Ee Ars'—or pretend DERs it's a real word pronounced like the name of the lanky dude from Workaholics.

But what does it mean?

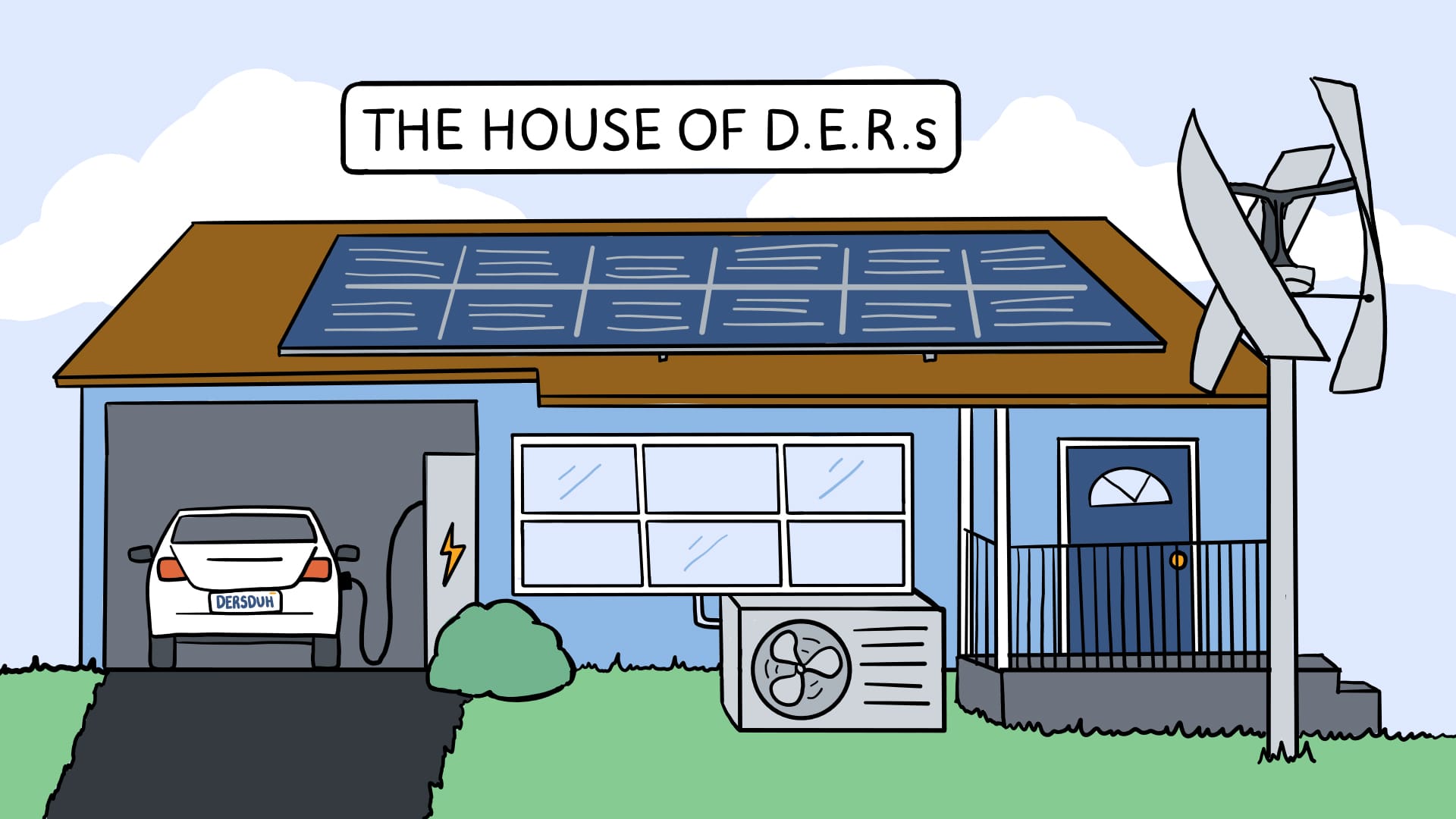

Energy Resources refers to any small-scale energy generation and storage technologies. Most of the time when we talk about DERs, we're talking about rooftop solar panels and home batteries. But there are lots of DERs in the world—small wind turbines, small gas power plants, diesel generators, thermal batteries, and more. An Electric Vehicle's battery can be a DER. An induction stove with a built-in battery can be a DER. Even an electric water heater can be a DER.

If it generates or stores energy and you can see it from your kitchen window, it's probably a DER.

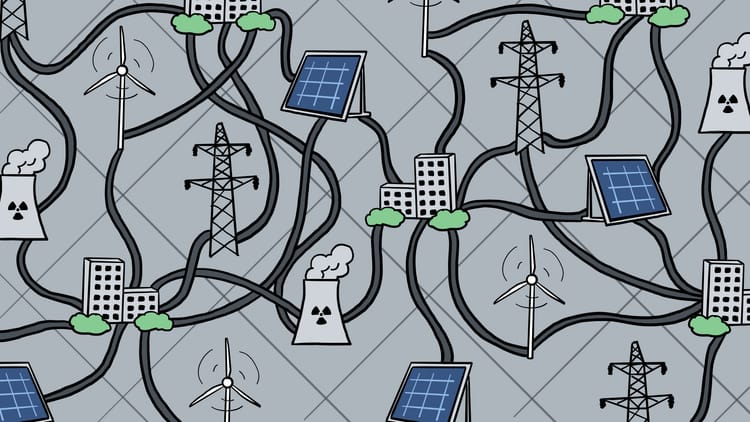

Distributed means these Energy Resources are not centralized but rather spread out across the land like dandelion fluff. The goal is to locate your energy systems in close proximity to where they will be used. That could mean on your roof, on the roof of a nearby school, in your garage, or in a field next to your giant data center.

So DERs just means 'build more rooftop solar'?

Not exactly. The basic premise of a DERs-first energy system is that if you distribute (or 'disperse', a word I like better) enough small-scale energy producers and storers, at some point they will collectively provide as much energy as their utility-scale brethren.

There are big benefits to keeping your energy system close to home. It's been said that electricity always takes the path of least resistance. This is evidently not true—electric current flows through any path available to it—but it's sort of true: the path of least resistance will always have the most current flowing through it.

That's all to say, having a community solar array next door to your house (or solar panels on your roof, etc.) effectively guarantees you'll always have access to fresh, sizzling hot electricity. Extrapolate and we can conclude that if our energy system was widely distributed, we wouldn't be so reliant on transmission lines like the Grain Belt Express piping in energy from out of state. The bulk of the power we use would be generated in our own communities.

To be clear, you would need a lot of DERs for this to work. But it could work. It's basic arithmetic, at the end of the day, and there are many rooftops in the world. Just ask Aladdin.

Or better yet, ask an Aussie. Australia has made it incredibly easy for folks to get rooftop solar panels, which has led to the highest rates of adoption in the world. Today, some 40% of Aussies have rooftop solar panels. 40%!

But I live in America where rooftop solar remains stubbornly expensive

Indeed, there are many obstacles to widespread DERs implementation here in the States. One of the biggest is that rooftop solar costs 3–4x more here than it does in many other places in the world. Much of that cost is attributable to our labyrinthine permitting processes. Americans routinely wait months (and pay hundreds of extra bucks) just to get approved to install solar on their roof. Meanwhile, down under, Australians can get same-day approval with a few taps on a mobile app.

America could do that, too—and increasingly, progressive-minded communities are. There's an app called SolarAPP+, developed by NREL, that expedites the rooftop permitting process. SolarApp+ is now being used in 160 communities nationwide. If you want it in yours, check out their website and start bugging your local reps.

The other obstacle to widespread adoption is that rooftop solar only makes since if you're a wealthy homeowner. No renter is gonna pay for an expensive and permanent upgrade to a building they don't own, and very few landlords will either, since their tenants would be the primary beneficiaries (as it's the renters' utility bills that would go down).

Does that mean we rentiers are totally excluded from the DERevolution? Not quite.

DERs for renters: power you can pack

Balcony solar

Something very cool is happening in Germany right now, and I'm not talking about Spargelzeit, the short season when Germans go crazy eating white asparagus.

No, I'm talking about how Germans are installing low-cost 'balcony' solar panels, AKA 'plug-in' solar, by the millions.

Unlike installing rooftop solar, which requires heavy machinery, roof inspections, dudes in hardhats grunting, an electrician to hook the system up to your building's electrical panel, and the aforementioned months-long permitting process, 'balcony' solar panels can be installed in minutes without any professional assistance. Just plug the panel into your wall outlet and hang it from your fire escape. It'll start soaking up the Bavarian sun and feeding energy into your home, offsetting some of your household's energy demand. Then, when your landlord jacks up the rent by 20% for no reason, just unplug your panel and take it with you to your next humble abode.

The tradeoff, of course, is you get less power out of fewer panels. Two balcony solar panels can provide up to 800 watts, whereas the average rooftop installation of 20–25 panels provides ~7 kilowatts—nearly 10 times as much power. But 800 watts ain't nothin'! That's enough to offset charging your laptop or powering your kegerator.

Balcony solar panels cost a few hundred bucks a pop, but like essentially all clean energy technologies, they'll pay for themselves eventually by lowering your utility bill every month.

And now, to disappoint you. Balcony panels aren't totally legal in the U.S. (regulations vary by state and utility). Utah, of all places, is trying to change that. They've passed a balcony solar bill with bipartisan support that just needs the stroke of their governor's pen to become law. But other regulatory headwinds remain—we still have no UL standards for plug-and-play solar, for instance—and our federal government has no interest in expediting balcony solar into existence. Yet the gears of progress begin to turn...

Bite-sized home batteries

There is something cool and legal with enormous potential to shift the DERs landscape for renters and homeowners alike: miniature home batteries, AKA 'backup' batteries.

Meet Pila, a sleeker, slimmer version of the traditional wall-mounted home battery. About the size of a DVD player, the Pila battery can fit inside a TV cabinet or hang out on top of the fridge. Like balcony solar, Pila doesn't require professional installation or permitting. Just plug Pila into the wall, plug your devices into Pila, and let the free app automatically save you money by powering your stuff with battery juice whenever electricity gets expensive.

Video from pilaenergy.com

Of course, you're sacrificing storage capacity by going with a smaller battery. The Tesla Powerwall, the best-known big home battery, has a capacity of 13.5 kilowatt-hours. Pila's capacity is 1.6 kWh. Still, that's enough energy to power your fridge for 32 hours during a blackout. And if you need more storage, Pila batteries can be stacked and/or work in harmony from different rooms in the house.

With an initial price point of $1,299, the Pila battery doesn't come cheap. Without subsidies, most of us renters will still be priced out of adoption.

However, I strongly suspect that in a year or two we'll see a surge of bite-sized battery competitors flooding the market at a variety of price points. They might not all look as pretty as Pila, but it's the utility that counts.

Right, so, to recap: if we all buy solar panels and batteries, big or small, then collectively we'll generate enough energy to become self-sufficient. We won't need any more expensive transmission lines that we can't build anyway, and the greedy utility companies will all be screwed. Hell to the yeah!

Except... it's not so simple.

Someone's gotta shepherd the DERs

Millions of DERs = grid chaos

Unfortunately, plugging a million solar panels and batteries into the grid would cause it to freak the fuck out. Our grid wasn't built to accommodate a vast, decentralized network that can send energy into the grid as well as pulling it out (i.e. 'bidirectional flow'). The grid was engineered for a limited number of predictable, utility-scale energy producers. Power is supposed to flow from the top down.

Not helping matters: our grid is rather stupid.

If you read the Green Juice series on utility companies, you may recall that forecasting next-day energy demand is a critical part of how all this works. Every day, the organizations that operate the grid (the ISOs and RTOs) do all this guesswork to figure out how much energy everyone's gonna need tomorrow. They have to do it that way because we have comically low visibility into real-time grid data.

A lack of real-time data means that if a fault or overload on the grid occurs, we won't immediately know where. If a piece of the grid starts to break down, it can go unnoticed until it's too late. We can't manipulate the grid to send electricity from an area where there's too much of it to an area where there's not enough. We are in the dark about far too much of this vital system.

Plopping millions of tiny moving parts on top of all that would result in pure chaos.

But what if DERs could act more like utility-scale power plants?

Virtual Power Plants

Virtual Power Plants, or VPPs, are like a school of tiny fish that arranges itself into the shape of one giant fish.

Put another way, a VPP is a DERs aggregator. I know that's kind of hard to wrap one's head around, so here's an illustrative dramatic scene:

One day, a traveling salesman knocks on your door. He says he's noticed you've got rooftop solar panels and an EV in the driveway. He invites you to join his company's Virtual Power Plant. All you need to do is let him install a smart meter on the side of your house (paid for by his company, naturally). Then, once a month forever after, you'll get a check in the mail for a modest sum—maybe $100 to $300 over the course of a year (though it can be more or less, depending on the program structure and where you live).

What's the catch, you ask, clinching your bathrobe tight?

There's barely any catch, he says! You'd be joining a network of hundreds of other homes just like yours. All his company does is skim just a liiiittle bit of energy off the top of your EV battery and take just a liiiittle bit of the solar power you generate. Such small amounts, you'll likely never even notice they're missing. At the most, maybe a couple times a week for half an hour your thermostat will move from 72 to 73.

By doing this with every house in their VPP network, his company can pool enough energy that utility companies will buy it off them when demand is high and electricity prices spike—just as though they were a gas peaker plant. His company pays you a portion of their profits. It's a win-win! They can sell energy without having to produce it, and you get some walking-around money (plus the satisfaction that you're helping keep the grid balanced for everyone).

Annnnd scene.

VPPs are still pretty new, but they're growing by leaps and bounds. By some estimates, VPPs could tackle 10–20% of peak electricity demand by 2030.

'Okay, that's cool, but I thought this was a post about clean energy opportunities for renters? All you've given us are solar panels we can't legally buy and batteries we can't afford!' my reader lambasts me.

'And furthermore, aren't VPPs just a continuation of our existing top-down energy system? A system in which a powerful minority population assumes all the control and benefits? Aren't you just replacing for-profit utility companies with wealthy homeowners?'

Astutely noted, reader. You certainly have a point.

And I have a response. But you'll have to wait till next week to hear it.

Member discussion